Grin City Artists Tackle Tough Questions with Social Crossings Toolkit

By Michael McAllister

Is it the duty of art to disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed? Some people say so, employing an assertion that exists in a variety of forms, attributed to people as diverse as 19th century journalist Finley Peter Dunne and modern-day graffiti artist Banksy.

Regardless of its origin, the sentiment lies behind Grin City Collective’s Social Crossings toolkit, the second portion of the collective’s summer 2017 project, a companion to the Community Resource Guide, part of the Map of Things No Longer Here.

“Art’s power includes opening up possibilities and actions from the heart,” states Purvi Shah, one of the artists behind the project. “We [she and her two colleagues] are honored to partner with Grin City Collective and the Grinnell community to nurture more belonging and justice into the world.”

The Creators

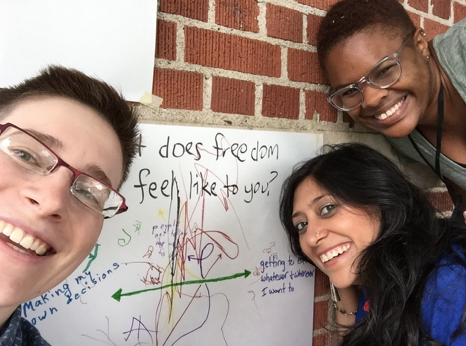

The artists who developed the project, pictured above in a photo from the toolkit, are (clockwise from the top) Keva Fawkes, Purvi Shah, and Anna Swanson.

Born in the Bahamas, Keva Fawkes currently studies at the University of Iowa in the Ceramics Department where she pursues her MFA. She describes her work as exploring “identity, immigration, and cultural imagery using found objects and architectural references.” She has exhibited both locally and internationally.

Purvi Shah, of Brooklyn, New York, originally from India, is a veteran artist, writer, poet, activist, and social justice advocate. Her work has garnered several awards. Previous projects have included participation in Grin City Collective’s public writing displays of 2015. Talking to Rob Dillard of Iowa Public Radio at that time, she stated that the project was “a way for language to be alive” and that the three poems she composed for display on library windows could never have come out of Brooklyn; instead, they were the product of an Iowa environment.

Portland, Oregon, is currently home to Anna Swanson, a filmmaker, writer, and teacher concerned with “spaces of experience in which transformation can happen.” On her website, she writes that she tries “to guide the chaos of the world into a smaller, flexible structure in which it can be seen anew,” adding that, in the process of creating, “reality bumps into me on every side.”

The Purpose

So the artists came to Grinnell and set to work.

They researched Grinnell’s history, especially interested the town’s connection to the abolitionist movement and its role in the Underground Railroad, with the help of library archives and interviews with residents. They asked questions about the past and questions about today.

“We thought of our current moment in American history—rife with divisions around race, immigration, who people can love, the role of government in our lives, and whose lives matter,” the artists report.

Thus they did not avoid difficult questions.

For example, the artists write in the toolkit that “We noticed how… White community members rescued enslaved people but didn’t want Black children in their schools.” They explored “various divisions current in the Grinnell community—town & college, the north and south parts of town.” They applied their observations to the current climate in America, asking additional questions about race, immigration, and social norms.

The ultimate purpose of the project was to generate conversations and “to enable a renewed spirit of abolition in Grinnell,” states the toolkit.

The Railroad

The abolitionist spirit of Josiah Bushnell Grinnell and Grinnell’s part in the Underground Railroad served as touchstones for the artists behind the project.

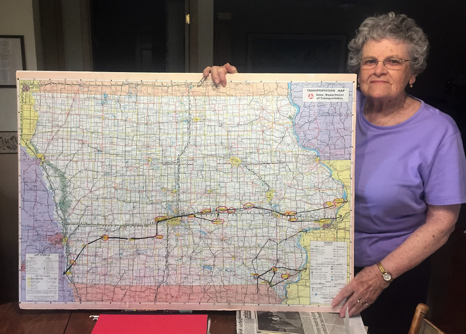

As the collective members researched Grinnell’s past, resident Thomsa Haas, pictured above, proved invaluable.

She was “a real treasure trove of knowledge and insight,” stated Anna Swanson.

A Grinnell resident since 1966, Mrs. Haas once was not especially interested in history—she holds an advanced degree in Christian Education from Union Theological Seminary in New York City—but she became a chronicler of the Underground Railroad nonetheless.

“She and I really connected,” Swanson reports, and the two women intend to stay in touch as they continue to research issues related to PIC, an acronym for the prison-industrial complex.

Through relationships such as that of Swanson and Haas, the work of Social Crossings can continue.

The Process

I identify as____________________________.”

That fill-in-the-blank statement is telling because people did not used to identify; people simply were.

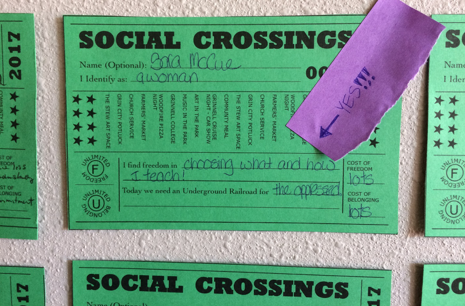

The statement was the second response suggested to participants on the Social Crossings “ticket”—patterned after the train tickets of yesterday—that the artists asked community members to complete during the first week of the project. Tickets were color coded to correspond to four quadrants of the city, roughly but not entirely along the lines of the city’s four wards.

Responses varied. I identify as…

- A farmer

- Mom, Grandma, Sister

- Female

- Human

- Male, White, Hispanic, Straight

- Hindu, American, Female

- An old woman

Other responses on the ticket came from similar partial sentences such as “I find freedom in _______________” and “Today we need an Underground Railroad for ____________.”

Once participants completed their tickets, the artists arranged them in the toolkit so that the juxtapositions would prompt reflection. Tickets were also displayed on the walls of The Stew during the project’s community potluck.

“Imagine a conversation between these two community members…,” the toolkit instructs, adding other prompts:

- What resonates?

- What feels difficult?

- What actions does this crossing inspire in you for equity and justice?

- What did you learn?

The Testimony

| Flanked by project participants Tilly, far left, and Ellen, far right, the artists pose, symbolizing community involvement: from second left, Keva Fawkes, Purvi Shah, and Anna Swanson. |

To explore the attitudes of Grinnellians today, the artists went into the community. They worked with representatives of Grinnell College, area churches, the Grinnell Area Arts Council, and Grinnell Heritage Farm. They spoke to residents at community events such as the Farmers Market and Music in the Park. They conducted lengthy interviews—some nearly five hours—with participants, and they distilled comments into a major section of the toolkit.

What is it like to be from somewhere else and come to Grinnell?

The toolkit reports 14 detailed responses that reflect on the experiences of people from diverse backgrounds over time. Excerpts tell stories and raise questions.

- It was a huge culture shock because all my life I’ve been around a variety of color and then moving here where it was predominantly White…. Even my children were like, “Where’s all the brown and Black people?”

- Especially for students of color, being in the town of Grinnell can be an oppressive and scary time, to not see any other—to go to the grocery store and you are the only Black person there….

- Three times in one place, people called me a dyke

- All the way around, people [in Grinnell] are nice, accepting, very accepting town—more like family-oriented around here.

- We have homeless people here. I know where they sleep cause I drive by them. And I’ve talked to them.

- If you don’t see racism, then you’re part of the problem because you’re keeping it squashed and you’re hiding it.

- There is nobody that is vetted like a refugee…. You are vetted. You have to go and get health checkups—you have to get all kinds of tests….

- It’s the first time I’ve ever seen the stars.

The Results

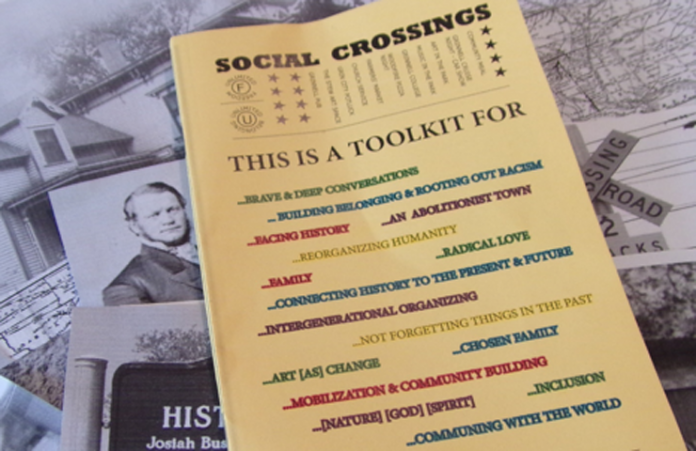

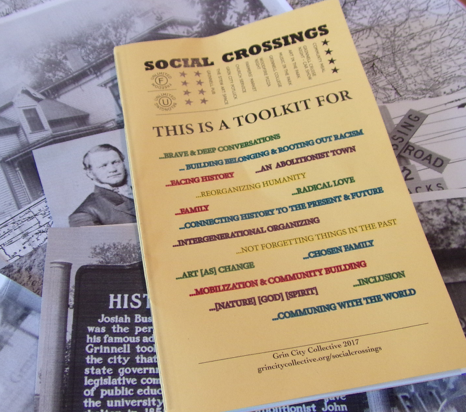

Keva Fawkes, Purvi Shah, and Anna Swanson came to Grinnell with ambitious goals—everything from promoting “brave and deep conversations” to “not forgetting things in the past” to encouraging “communing with the world.”

Their Grinnell residency culminated in a community potluck held on the evening of June 30 at The Stew gallery at 927 Broad Street.

They made the tangible result of their residency—the Social Crossings Toolkit—available at that time, but much of what they sought was intangible.

Did they accomplish their goals?

“I would say yes, absolutely,” answers Anna Swanson. “We have done our best to honor the voices and experiences of folks of color in Grinnell, and to bring together a room full of people for our final Community Social that would likely have never all been in the same room otherwise.”

Keva Fawkes reports, “I was delighted to find so many community members willing to share their experiences and time…. I believe we have been successful in bridging Grinnell’s history of the Underground Railroad and its presence in present day Grinnell.”

“We need conversation and community—especially these days,” states Purvi Shah. “My hope is that Grinnell communities continue to draw upon the Social Crossings toolkit to have brave conversations and feel emboldened to take actions—until we all are fully free.”

The Track Ahead

Is it the duty of art to disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed?

No doubt Anna, Keva, and Purvi would answer affirmatively.

And, even though the June 30 community potluck capped the artists’ physical residency, they stress that the project did not end that evening.

Among the action steps called for by the tooklit are the following:

- Talk about race and inequality.

- Connect the past to the present to the future: correct harms while creating the world we want for our future generations.

- Believe in the power of community and collective belonging.

- Find joy, spiritual connection, fun, and love….

The following links will enable those inclined to maintain social crossings with Grin City Collective and with the artists.

Some questions defy simple answers. Some questions take years—decades—to answer. Some questions may never be answered.

But projects such as The Map of Things No Longer Here and publications like the Community Resource Guide and the Social Crossings toolkit ask the questions. And that is the first step.